Radical Journalism

& Party Building

in 1961 in the peace and civil rights movements, and

soon became a leader in the student movement. I went

on a Freedom March in Mississippi and afterwards was elected a national leader of SDS in the years 1966-68.

Next I was a journalist at the Guardian in New York,

and travelled to Cuba and China. Later I worked with

several groups trying to create a new communist party.

By the late 1980s, with the global crisis in socialism

and the dawn of the information age, I decided the old

dogmas had to be set aside. I began working on a new

theory of change...

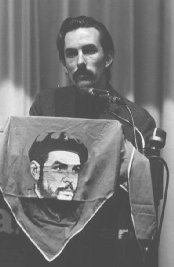

Speaking together with

H Rap Brown of SNCC at Guardian Anniversary

The Weeks that

Changed My Life

Minister in Beijing, China

National Guard

Tanks outside

SDS office on

West Madison

after ML King Assassination.

We marched in groups up and down the street, telling the soldiers to 'shoot in the air if you have to, but don't kill for the slumlords.'

Freedom Bus: From Hopewell to Alabama

White Man Worked to Help Blacks Get Rights

By Bob Bauder

Times Staff

In the spring of 1966, Hopewell Township's Carl Davidson was living in the black section of Lincoln, Neb., about to embark on a journey through the South that would change his life forever.

Davidson, a national leader in civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements during the 1960s, got his first taste of tear gas and billy clubs while participating in a march from Memphis, Tenn., to Jackson, Miss.

James Meredith's March Against Fear, which began June 5 as a solitary walk for black voting rights, became a national event when a racist sniper wounded Meredith on the second day.

The shooting attracted civil rights leaders and supporters from across the nation, including Davidson, who scrambled to carry on where Meredith left off. For three weeks and 220 miles, a stream of protesters snaked across Mississippi, clashing with police and white mobs several times along the way.

It prompted Davidson to describe Mississippi as "a mockery of everything about the America that I was taught to love and be proud of."

"As you know, the experiences I had in Mississippi earlier this summer affected me quite a bit," Davidson wrote in a letter to his mother. "Somehow, after witnessing that brutality, I am just not able to return to my sheltered life within the comfortable walls of the university, at least not for the time being."

The "time being" lasted forever. Davidson never returned to the University of Nebraska's comfortable walls.

"It changed my life," Davidson said 36 years later, recalling those sweltering days and fearful nights in Mississippi. "I became thoroughly dedicated to stopping segregation. It wasn't part time after that."

He got himself elected national vice president of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a left-wing campus group dedicated to stamping out segregation and stopping the war in Vietnam, and he continued to rise within the organization. By 1967, he was one of three SDS national secretaries.

His contemporaries were leading radicals of the day - Tom Hayden, Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman and Bobby Seale - and he traveled the world preaching against U.S. policies at home and abroad.

It was a bold endeavor, especially for a white guy from conservative Hopewell Township, where farmers just about outnumbered the black population in the early 1960s. Davidson suffered plenty of criticism from back home, but he always had the support of his mother.

"He had his own mind, but there wasn't too much I didn't agree with," said Lolita Pinti of Aliquippa. "I thought he was doing the right thing. That's just about what he wanted to do - save the world."

The time spent in Mississippi laid the foundation for a career.

"I'm still at it," Davidson, 59, said in an interview from his home in Chicago, where he teaches minorities how to operate and repair computers.

Seeds of dissent Davidson didn't set out to save the world. He grew up around his father's service station in Hopewell with a knack for mechanical drawing. In high school, he designed a rocket that won a national scholastic aerospace award, and his mom said he was smart enough to do anything he liked.

"I think he was smart enough to be president of the United States," she said.

But seeds of dissent were also sown in high school, where he first crossed racial lines through a common interest: jazz. Hopewell High School was integrated, even in the 1950s, but black and white students rarely mingled.

"There were probably lots of problems with racism, but we (whites) just didn't see it," Davidson said. "I was into jazz, so I had a lot of friends who were black. We used to hang out at the Del Sha lounge downtown on Franklin Avenue (in Aliquippa). It was the only bar in town that had a lot of blacks and whites together because it was a jazz bar. It was kind of a beatnik bar, the true beatniks: Korean War veterans who were mostly alienated."

They exposed Davidson to a darker side of America, one that condoned separate and unequal status for blacks and whites, the Ku Klux Klan and lynching.

Davidson carried his Del Sha's experience to Penn State University, where he enrolled after graduating from Hopewell in 1961. The civil rights movement was gaining momentum, and students across the nation were becoming more and more involved.

Davidson watched as violence erupted between blacks and whites in the South, and he decided he had to act. "When I got to campus and I saw the Birmingham police turning the dogs on people, I took it personal," he said.

He joined the Friends of SNCC (pronounced snick), a campus group that supported a parent civil rights organization known as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

SNCC arose from student sit-ins sweeping the South during the early 1960s that targeted segregated public facilities. By 1966, its leader was Stokely Carmichael, who would eventually proclaim black power throughout the land.

Davidson also joined the SDS, which began as a civil rights group and evolved into an anti-war movement.

As a support group, Friends of SNCC raised money and sponsored educational programs in an attempt to make people aware of what was happening in the South. The money funded things such as black voter registration drives, Davidson said.

"Mainly we brought in speakers from outside," he said. "Then we had literature tables. We would try to promote different visiting speakers and programs, educational stuff. The kind of stuff we did was relatively low-key, but it was hot for the time because nobody was doing it before."

The organization used similar methods to raise money.

"We would set up a table in the student union building," Davidson said. "I remember we used to have this one student who was a very segregationist guy, and I used to love when he came around. We would always argue. The longer he would stand there and argue, the more money would go into the pot. He was inadvertently one of our best fund-raisers."

In 1965, Davidson and several other Penn State students headed south to join the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders on the march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., which became one of most poignant moments in the civil rights movement.

Mounted police attacked marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge just outside Selma. The beatings and tear gassing at the bridge and subsequent confrontations were carried via television to living rooms across the country.

En route to Selma, the car carrying Davidson crashed on an icy road near Knoxville, Tenn., landing Davidson in the hospital with a fractured vertebra. He said some of the others eventually made it to the march while he sat in the hospital.

A year later, however, he got another chance. This time it was Mississippi, the most segregationist state in the union, and one with a penchant for murdering civil rights workers.

Black power James Meredith, the 29-year-old son of a Mississippi farmer, gained national fame in 1962 when he became the first black to enroll in the segregated University of Mississippi. The event touched off riots by white mobs, which threatened to lynch Meredith. Federal troops were eventually dispatched to quell the unrest, and Meredith went on to graduate in 1964.

By 1966, he was a civil rights leader. He began a solitary march along Route 51 there to show blacks in his home state that they had nothing to fear by registering to vote. A gunman ambushed him on June 6 in Hernando, Miss., wounding him with a shotgun blast.

Civil rights leaders, including King, Carmichael and Floyd McKissick, the leader of the Congress of Racial Equality, decided to continue the march.

Davidson was in graduate school at the University of Nebraska, where he had set up a SDS chapter, when he heard about the Meredith shooting.

"We had a little SDS house that we rented in Lincoln, Neb., in the black community," he said. "We were talking to these older black guys, our neighbors, and we got the news about Meredith being shot. We said, 'Let's go.' We got about eight people together and we went. It was something that was just decided in about an hour."

Davidson drove to Memphis, where his group met up with the other marchers at a church that was serving as a staging area. It was across the street from an innocuous place named the Lorraine Motel. Two years later, King was assassinated on a balcony of the motel.

Davidson recalled stifling heat, dusty roads and almost passing out from dehydration during the march. The number of marchers would swell as the parade came upon towns along the road, but the central group numbered about 500. Davidson said farm laborers would drop their tools and walk along when the march passed them in fields.

Each night, the marchers would camp in and around black churches and homes, and the leaders would rally them with speeches.

"King was an incredible speaker. There wasn't any better," Davidson said. "How he managed to combine biblical cadences with contemporary politics, it reminded me like what the Old Testament prophets must have been like."

But the most famous speech wasn't King's. The speech that made headlines happened on June 16 when Carmichael, who had recently been released from jail, evoked "black power." People had been hearing about black power for a while, Davidson said, but this was the first time news reporters picked up on it.

It was the first time white America had heard the phrase, and it reverberated through the white communities with fear. Carmichael was later accused of being a racist.

"It was electrifying," Davidson said. "I remember we were sitting out in a little black church, and it was full of sharecroppers, people who picked cotton, wearing their bib overalls. Stokely Carmichael got up there and started telling people that nappy hair was beautiful, that black skin was beautiful. He said the one thing that black people needed was political power - black power - and it just went like electricity through the church.

"I was surprised when I got back North and heard about the negative reaction to black power. It didn't make any sense to me. People were afraid of it. What I saw was the reaction of these black sharecroppers, the pride in their faces when they heard Stokely Carmichael talking about black power. It had nothing to do with racism. It had everything to do with people who were oppressed for a long time."

Davidson, who could type and had writing skills, was given the job of typing press releases and communications. Once the marchers entered Mississippi, he said, marauding white patrols cut off telephone communications in the rural towns. The only way of communicating with the outside world was through letters.

Things got ugly in Canton, Miss.

The principal of an all-black school let the marchers sleep on the grounds one night, and the police were determined to roust them. Mississippi state troopers showed up and began firing their guns into the air. No one was shot, but plenty of people were beaten, and the troopers fired tear gas into the crowds.

"I got pushed around with a billy club, and I got tear-gassed," Davidson said. "They were just basically harassing us. There was no reason why we shouldn't have been allowed to sleep on that school ground. We ended up going to a church somewhere."

On June 25, Meredith joined the march just outside Jackson, and the following day, the marchers triumphantly reached the city.

"Years later, somebody sent me over to UPI (United Press International) to get some pictures," Davidson said. "I was looking through the UPI photo files, and I found a picture of the tear-gassing. I have it hanging on my wall in the bedroom. I'm sure there were a lot of other things that happened on that march that I can't remember now. The main thing was they couldn't stop us."

After Mississippi, Davidson dedicated his life to combating social injustice. Among other things, he worked as a reporter for the leftist Guardian newspaper in New York City before settling permanently in Chicago.

Today he is working against what many call the digital divide, the gulf between people who know how to use and have access to computers and those who don't. He teaches minority children and adults who have been recently released or are about to be released from prison how to use and repair computers.

He laughs when asked whether he's still trying to save the world.

"That's the civil rights issue of the 21st century," he said. "Some people have access to information technology and how to use it, and some people don't. When you don't, you're kind of put into an economic ghetto."

[Bob Bauder can be reached online at bbauder@timesonline.com.

ęBeaver County Times Allegheny Times 2005]