| Archive: Issue 7 - Spring 2001 |

||

How

the Internet is Changing Unions

(page 1 of 2)

By Eric Lee Working USA

Some unions will point to such things as cost savings. There's no question that email is cheaper than fax, telephone and old-fashioned postal mailings. Cost is often cited by trade union officials as a reason to invest in any new technology, including the net. But I think his misses the main point, which is the role played by the Internet in reviving and strengthening the labour movement. There are three major effects which I intend to address in this article:

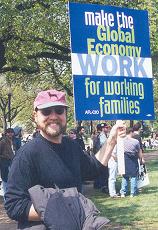

There is little debate any more about how much the Internet has changed the world -- it is now widely understood that the emergence of a global computer communications network is an event comparable to the invention of the printing press. (Though I do think comparing the net to the discovery of fire are stretching things a bit.) It has changed much in the world we live in, including how we buy and sell things (from books to shares on the stock market), how we learn and teach, how we are entertained and informed. Everyone who uses the net understands this. It is a tranformative experience. And it is changing trade unions too, even if they don't realize it yet. It's a little hard, at first, to accept the idea that new communications technologies change institutions like trade unions. And yet a glance backward at the 19th century reveals that the telegraph too had a profound effect on the world's economy and culture and even -- albeit somewhat less obviously -- on the emergening trade unions. In Tom Standage's delightful book, The Victorian Internet, a history of the telegraph, he recounts a story of the first trade union meeting conducted "online" -- hundreds of employees of the American Telegraph Company working the lines between Boston and Maine met for an hour, conducted their discussions and even passed resolutions, all in Morse code. Obviously the idea of "online" trade unionism (using Morse code) didn't catch on in the 19th century. But no less an authority on the early labour movement than Karl Marx was convinced of the transformative power of new communications technologies. In The Communist Manifesto, he wrote that it was not the occasional victories of workers that was the "real fruit" of their struggles, but the "ever expanding union" of workers. "This union," he wrote, "is helped on by the improved means of communication that are created by modern industry, and that place the workers of different localities in contact with each other." New communications technologies create new possibilities for trade unions. In the nineteenth century, they made unions possible -- or at least unions that went beyond a single location. National trade unions, which were common by the end of that century, would have been unthinkable without the national economies, which were in turn dependent upon the telegraph. The global trade unions emerging today, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, are being made possible because of the Internet. But none of this happened overnight. There is a history going back more than twenty years of trade unions using computer networks. The global networked trade unions now being born have their roots in the early 1980s. Back in 1981, personal computers were hobbyists' playthings. They existed. Some people bought them. Some hobbyists even built modems, which allowed them to exchange files through telephone lines. In the late 1970s, electronic bulletin boards had been created. But you really had to like this sort of thing to buy and use a computer at home. Trade unions, of course, had nothing to do with any of this. They continued to work in the old tried-and-tested ways (without using computers) for years to come, lagging far behind businesses, which adopted personal computers widely in the 1980s and got online by the mid-1990s. But in 1981, there was a first, tentative step made. Larry Kuehn and Arnie Myers of the British Columbia Teachers Federation (BCTF) saw a demonstration of how a modem worked and were impressed. They introduced portable computers (not very portable by today's standards) with modems and printers to union leaders and quickly created the first labour network. Soon the whole Executive of the BCTF was traipsing around the province sending off messages to each other on the clumsy machines. There was no rush of imitators even though the project was fairly successful. (The union survived a brutal assault by the right-wing provincial government in part because its internal communications allowed swift and effective responses.) By mid-decade, a fellow Canadian -- Marc Belanger of the Canadian Union of Public Employees -- managed to put together Canada's first nationwide packet-switching network. It was not only the first such network created for a union -- it was the first such network created in Canada, period. It was called Solinet, short for Solidarity Network. Within a short time, hundreds of CUPE members were using Solinet's unique conferencing system which was also the first in the world to work in two languages, English and French. Meanwhile, the need for cheap communications was driving European-based International Trade Secretariats to seek out alternatives to phone calls and even the new fax machines. (International Trade Secretariats are global organizations of trade unions in particular sectors of the economy, such as teachers, metal workers, transport workers and so on.) Eventually, they came upon a German-based network called Geonet and began using this to exchange emails and even set up online bulletin boards. The ITS for the chemical sector -- now known as the ICEM -- and the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF) were pioneering global labour computer communications years before most of us were even using personal computers, let alone the Internet. A little more than a decade after Kuehn and Myers got hooked on the idea of modems, enough was happening to justify an international conference to discuss where things were going. This was held in Manchester in 1992, hosted by one of Britain's largest unions, the GMB. That Manchester conference and a successor one in 1993 included among the invitees all those who had been involved -- including Kuehn, Belanger, and the Europeans, such as Jim Catterson of the ICEM and Richard Flint of the ITF. Poptel, a workers cooperative had been launched in the UK to help coordinate this work, and a rival grouping in the US -- IGC Labornet -- set about to bring American unions online. For several years the two systems -- Geonet's and IGC's -- existed side by side, unable to communicate with one another, offering rival conferencing systems for those few trade unionists who were already online. I got interested in all this sometime in 1993. The International Federation of Workers Education Associations (IFWEA), which employed me to produce its new quarterly "Workers Education", took a great interest in these new developments. It became the first international labour body to have its own website, early in 1995. I began contacting all the early pioneers who had been making slow progress for more than a decade, learning about this remarkable hidden history of an emerging labour network, when suddenly all hell broke loose. Thanks to the creation of the Mosaic browser in 1994, the Internet became, overnight, a mass medium. (The Mosaic browser is the forerunner of Netscape Navigator.) In my book, The Labour Movement and the Internet: The New Internationalism (Pluto Press, 1996), I pointed out that the most optimistic estimates showed then about 50 million people online. The day was coming, I wrote, when there would be double that number. As I write these words, early in 2000, there are over 200 million people online. Many millions of these are trade union members and thousands of unions have established websites and begun using the Internet as a basic tool of communication. Coincidentally, many of the countries with the highest rate of Internet penetration, such as Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, are countries with the highest rates of trade union organization. Thus the percentage of Internet users who are trade unionists is actually probably quite high, and it is not unreasonable to suggest that there are currently tens of millions of trade unionists online. Now that the net has become a mass medium, it's time to look at how it has changed trade unions. Some unions will point to such things as cost savings. There's no question that email is cheaper than fax, telephone and old-fashioned postal mailings. Cost is often cited by trade union officials as a reason to invest in any new technology, including the net. But I think this misses the main point, which is the role played by the Internet in reviving and strengthening the labour movement. There are three major effects which I intend to address in this article:

The most important of these, by far, is the first -- the re-internationalization of the labour movement. One has to start by remembering how bad things have gotten. A hundred years ago, there existed a kind of labour internationalism that is hard to imagine today. Working people often dug deep into their pockets to support far away strikes and unions were often built by highly mobile workers who moved from country to country. The ties between unions in different countries were much stronger in 1890 than they were in 1990. In 1890, unions were able to organize centrally co-ordinated worldwide protests including general strikes in support of a single, global demand -- the 8-hour day. And they were able to co-ordinate their actions so that it all happened on a single day: May 1, 1890. That was the first real May Day. It would have been unthinkable a hundred years later to organize a similar global campaign, even though communications technologies were much improved. American unions have been particularly affected by the de-internationalization of the labour movement and for many years, the heavy hand of the AFL-CIO's International Affairs Department held back any kind of genuine solidarity campaigning, particularly at rank-and-file level. And this was not only true of the USA, but of most trade union movements in most countries. International departments of unions talked to one another; ordinary workers did not. The Internet has already had a huge impact and one can now say without fear of exaggeration that it has contributed to a remarkable re-internationalization of trade unions which has in turn empowered those unions, allowing them to survive and grow in the most difficult of times. A remarkable example took place in early 1998 when tension between Australian dock workers (known as "wharfies") and their employers, backed by a viciously anti-union government, peaked -- launching what came to be known as the "war on the waterfront". News was breaking every hour as unions, employers and government fought it out in the country's courts -- and in ports around Australia. The Maritime Union of Australia, representing the wharfies and the target of vitriolic hatred from the right, had just launched its own, slick website. But it wasn't being updated. Like so many trade union sites, it was just an online brochure. A team of web activists from other unions, including the teachers, worked together with the Australian Council of Trade Unions to get up a regularly updated site on the net, but even this proved to be a sporadic effort. The most successful attempt to maintain daily coverage on the web was done by a local activist in Melbourne, an anarchist who went by the online name of Takver. His "Takver's Soapbox" website, together with the Leftlink mailing list run out of a leftist bookshop, became the best sources of up-to-date, online information about the dispute -- which increasingly took on an international character. More >>

|

||

| |

||

WELCOME!

You are visitor number |

Designed

by ByteSized Productions © 2003-2006

Now

that the net has become a mass medium, it's time to look at

how it has changed trade unions.

Now

that the net has become a mass medium, it's time to look at

how it has changed trade unions.